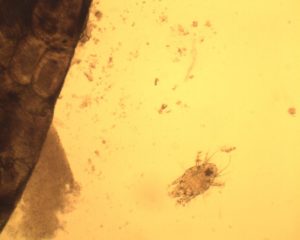

It is thought that the Tracheal mites (also known as Acarine) was a major contributory factor to the ‘Isle of Wight disease’ first seen in the early 1900s. It decimated the honey bee population, later spreading to mainland UK. In more recent times, the Tracheal mites have had a serious economic impact on the beekeeping industry in North America, after it’s introduction there in the 1980s from Mexico. However, in the UK Tracheal mite infection is not usually a serious disease, with relatively small numbers of colonies being affected.